“I’m a [software engineer, product manager, lawyer, analyst, so on] and I want to transition to climate work. Where should I look?”

I get a version of this question a lot. This note summarizes how I usually answer it in case it’s useful for folks asking a similar question.

Two approaches

In general, I’ve seen (and myself taken) two approaches to getting a job in climate. I’ll call them the ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ approach.

1: Bottom-up approach

This is the traditional way to find a job: you look for open positions at existing climate companies. When I decided I wanted to work on climate in 2012, I used the Kleiner Perkins portfolio page as a starting point to find promising, high-growth climate companies (at the time, Kleiner Perkins was one of the only VCs investing in climate). Opower and Nest were two of the companies that came out of that search, and I was lucky to eventually work at both.

If I were taking this approach today, here’s where I’d start (I’m sure there are other great resources out there, please send over and I’ll add them):

Look at the portfolio companies of top climate VCs, such as Lowercarbon, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Energy Impact Partners, G2VP, Prelude, Voyager, or MCJ. CTVC has a list of a bunch of other VCs making climate investments.

Look at climate job boards, such as Climate Draft, Climatebase, or CTVC.

The bottom-up approach can certainly work—it’s a tried-and-tested approach to job hunting. However, it’s definitionally limited to companies / solutions / roles that already exist. Given how early we are with climate (in the grand scheme of things), I’d argue that right now the bottom-up approach will miss quite a bit. This brings us to the top-down approach.

2: Top-down approach

The second approach starts by understanding the contours of the climate problem, identifying one or a few chunks for which your skills might be particularly well suited, and going deep to identify a specific part of the problem you want to try and solve. Let’s call this the top-down approach. While this approach will almost certainly feel messier than the bottom-up approach, it can lead to more creative, unexpected or novel opportunities.

This was the approach that led me to work on carbon removal at Stripe. I’ll start by sharing my own story as one example of what this can look like in practice, and then try to generalize it.

In 2019 I found myself with a lot of down time while at home in North Carolina helping take care of a sick parent. At the time I was working at a self-driving company. I’d known I wanted to get back to climate work eventually, but figured that would be in 5+ years. Separately, despite having worked in climate previously, I felt I no longer had a great grasp on the climate basics. So, with extra time and a self-prescribed need get back to basics, I picked up the 2018 IPCC report.

One of the jarring findings from the 2018 IPCC is the massive need for carbon removal (in addition to radical emissions reduction). This was news to me. I began consuming as much content on carbon removal as I could find. As I dug in, it became clear there really wasn’t…all that much to dig into. The gap between the size of the need laid out by the IPCC (gigatons per year by midcentury) and the existing state of solutions seemed enormous. The more I learned, the more I felt an increasingly urgent need to do something. It just wasn’t clear what.

My first instinct was to go deeper on the ‘supply’ side of carbon removal. Maybe I could work at an existing carbon removal company? At the time, Climeworks, Carbon Engineering and Global Thermostat were the main carbon removal companies and (rightly) focused on core technical challenges. I’m not a scientist or engineer by training and it wasn’t clear to me that I could be particularly useful to them.

So I moved over to the ‘demand’ side. In contrast to climate solutions like clean energy, carbon removal has no intrinsic value to the end buyer. Who is going to buy this stuff? Getting governments to either buy it themselves or create a compliance market through regulation emissions are obvious (and obviously important) solutions. But, alas, I am also not a policymaker (and, at the time, felt intimidated by policy work and skeptical of my ability to move the needle) so I ruled that out.

I reformulated the demand-side problem for myself to be: how do you build a market for carbon removal in the absence of policy?

I became obsessed with this question. I figured that two main options (outside of government) were individuals and businesses with excess income/margin. Around the same time, Christian Anderson at Stripe published a blog post announcing Stripe’s commitment to buy $1M of carbon removal, along with a very compelling theory of change. One of the things that made me especially interested in this idea coming from Stripe was the distribution potential. Stripe builds economic infrastructure for the internet, processing payments (among many other things) for millions of businesses all over the world—many of them high-margin SaaS businesses. If they could compel a fraction of them to direct a fraction of their revenue to carbon removal, they could potentially build a really big market for carbon removal.

I sent the post to Clay Dumas at Lowercarbon (a longtime friend and one of the people I’d been incessantly pestering with questions about carbon removal for the past few months). Clay offered an introduction to Ryan Orbuch at Stripe, who had volunteered to work on making good on that commitment (in addition to being a PM at the time) and at the same time was making the case for full-time headcount to focus on carbon removal. Fast-forward through a bunch of conversations, I joined Stripe to lead the carbon removal program.

Why am I sharing all of this detail? First, to illustrate the ‘messiness’ of what one example of the top-down process looks like in practice. Second, to make the point that: without a solid understanding of the problems facing carbon removal, I’m quite sure I wouldn’t have been able to see how enormous the potential to build a market for carbon removal at Stripe really was. A deep understanding of a climate problem can help you ‘spot’ great opportunities in sometimes unusual places.

Below I try to generalize the a process for taking this approach into ‘steps’ at the risk of making it seem more linear than it is. Read this to get the gist, but take it with a giant block of salt and use your own judgment to determine the right sequence for you.

Step 1: Orient yourself to climate ‘landscape’

The goal of this step is to learn the ‘minimum amount’ to identify the parts of climate that might be a good match for your interests and skills (and, conversely, which won’t).

Because climate touches most of the global economy, the trick is identifying these areas without having to understand everything about everything. There’s lots of great reading material out there (Watershed has a great reading list here). For the purposes of illustrating the top-down approach, I’ll refer to a short overview piece I wrote that attempts to provide a mental model for climate and break the climate problem into chunks for the remainder of the piece. Spend ~5-10 minutes reading A Mental Model for Combating Climate Change if you haven’t.

Step 2: Pick a few areas to ‘drill’

The goal of this step is to pick one or ‘chunks’ that you suspect might be a good fit. No need to get overly-precise about. Think about (a) what you’re naturally drawn to and (b) if you can imagine your skills being important to that area.

For example, if you want to work on consumer, Lever 1, Area 1 (from the mental model piece linked above) might be a good area to dig because we need to electrify people’s homes and lives: electric cars, induction stoves, and heat pumps all need to be the default. This area needs great folks in engineering, manufacturing & supply chain, storytelling & marketing, etc.

If you’re a data scientist or ML engineer, Lever 1, Area 3 could be a good area to dig because we need to figure out how to match much more electricity demand (from the electrification of cars, etc.) with intermittent supply (wind, solar, etc.).

And so on. I picked Lever 2, starting with Area 1 and then moving to Area 2.

Step 3: Drill deeper to identify a few gaps that need to be solved. Zoom in and out out until you find a problem you can’t stop thinking about and a path to solve it.

Go deep: read, talk to people, take field trips, be fearless about asking basic questions, revise your framing of the problem accordingly, and get creative about where you might be best positioned to solve that problem from. As Peter Reinhardt says, “the distance to the frontier is usually shorter than you think.”

Other considerations

Finally, a smattering of other considerations that you may find relevant as you consider different paths into climate:

“Does software even matter for climate?” I hear this a lot. Yes—software will play a critical role for many if not most pieces of the climate puzzle. The thing remember is just that software is not an end in and of itself. To impact the climate, any software must eventually change something in the physical world (ie CO2e in or out). When it comes to climate, it’s bits in service of atoms.

Startups aren’t always the right vehicle for impact. Speed and scale matter hugely for climate. For many parts of the problem, I could make a case that change is best made from companies that already have established competencies and existing distribution. For example, if Viking or Wolf decided to put their minds towards making induction stoves a priority, I’d guess they’d be able to scale them much more quickly than a startup.

Speed matters a lot. There’s a high discount rate for all things climate. Every year we delay has very large costs. “Good enough” now is often better than “perfect later.” If you’re thinking about working on climate now or later, now>later.

Creative financial instruments are under-explored vs their potential. Financial innovation will be critical to actually deploy the climate infrastructure we need globally. The car loan and home mortgage (both novel concepts at the time) quickly changed the landscape of American infrastructure. We’ll need that type of innovation, but at a much greater scale.

Sooner or later, you’ll probably need to ramp up on climate policy. I kept all things policy at arms length for a long time because it felt like a black box/I had zero policy intuition. But, as is the case with most things in climate, the scale of the problem means you can only ignore policy for so long. If you don’t know anything about policy or climate policy, no problem, it’s fortunately very learnable (and quite interesting!).

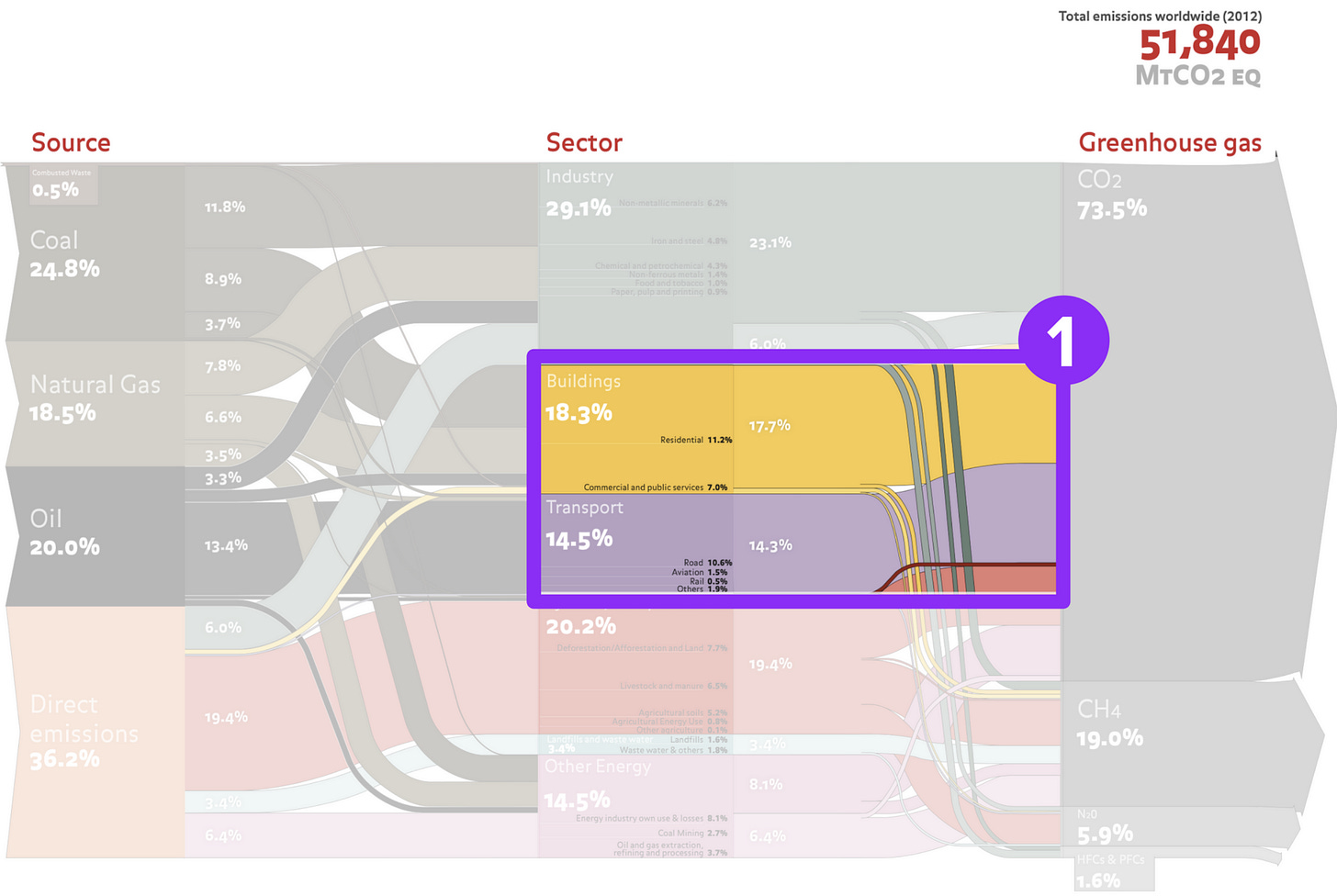

There isn’t a silver bullet—really. But don’t underestimate 2nd order effects when estimating impact. One of the most initially frustrating/disheartening things about dissecting the emissions flow diagram is realizing that there’s genuinely is no silver bullet. The problem breaks up into lots of little slivers. Questions like “how can I ever make an impact here? Will my work even matter?” are normal. But don’t underestimate 2nd order effects when estimating impact. If you look at the emissions reduction impact of Tesla alone, the result is not all that impressive. Tesla’s actual impact has been compelling all of the other car companies into electric transportation.

Fantastic overview, I have recently been collecting my own notes on this topic, now 2 years on my (passive) job hunt and will certainly share this with all my peers on similar journeys.

I have been mostly advocating for the top-down approach and especially for more senior roles where it benefits the job seeker to be more specialized in terms of area(s) of focus. I have found that getting plugged in (forgive the pun) to conversations has been easier when you bring something to the conversation. Show up with a point of view and look to have people challenge you as a way to sharpen your own perspective. This would seem to fit in around Step 3 in your prescribed approach here.

Great post!

Thank you for this article Nan! Two of the clearest options for pivoting your career into climate seem to be to join a company or to start a company. I'm wondering if you had any advice for getting your existing company to move into climate? It seems like you joined Stripe after they had already decided to take climate action but what advice would you have for someone trying to get their existing company to take the first step and incorporate climate into their product? Beyond tying the proposed program back to important business metrics, do you have any advice for convincing leadership to believe that it's worth investing in climate?

For context, I'm a PM at a later stage fintech called Petal and have been working on a feature that would allow our 300k+ members to remove carbon every time they swipe their Petal card.