GLP-1s but for attention?

Humans have a finite amount of attention. At any given moment, we can focus on a limited number of things, there’s only so much time in a day, and there are only so many people in the world—about 130 billion hours of waking life each day.

How we allocate that attention matters. We want to be humans, not zombies. To work on cool stuff, do things that haven’t been done before, read books, make things, love people around us, listen to them, and not have our mind snatched by a buzz against our thigh.

And, famously, the competition for our attention is fierce—TV, TikTok, Instagram, Twitter. Increasingly we see discussions of how there’s something vaguely cursed about the culture right now, and that feels related to everyone’s attention getting fracked. Said less spiritually, it just sucks to be addicted to stuff that doesn’t make you feel good. Most of us don’t really want to be scrolling TikTok or Twitter, but nonetheless the hours sometimes disappear.

We’ve all lost days to ennui, so did Mark Twain. What Mark Twain never lost a day to was YouTube Shorts.

So: if attention is finite and we’d like to be able to more easily and reliably allocate it to things that matter, is there more we can do to get it back?

To be clear, we are not making any normative assertions on what people ‘should’ be spending their time on. Rather, we’d like to end up in a world where people can more easily direct their attention towards what they want to spend time on. In other words, how do we radically ‘free up’ attention so people can spend it on activities of their choosing?

Food as analogy

Appetite seems like a pretty good analogy for attention. People want control over their appetite just as they want control over their attention. And both have become harder to control over time—appetite is more easily hijacked by ever-more-addictive, sugary food, just as attention gets hijacked by ever-more-addictive algorithms. Many people don’t want to eat—or watch—the things they do, but they do anyway (and then feel bad about it).

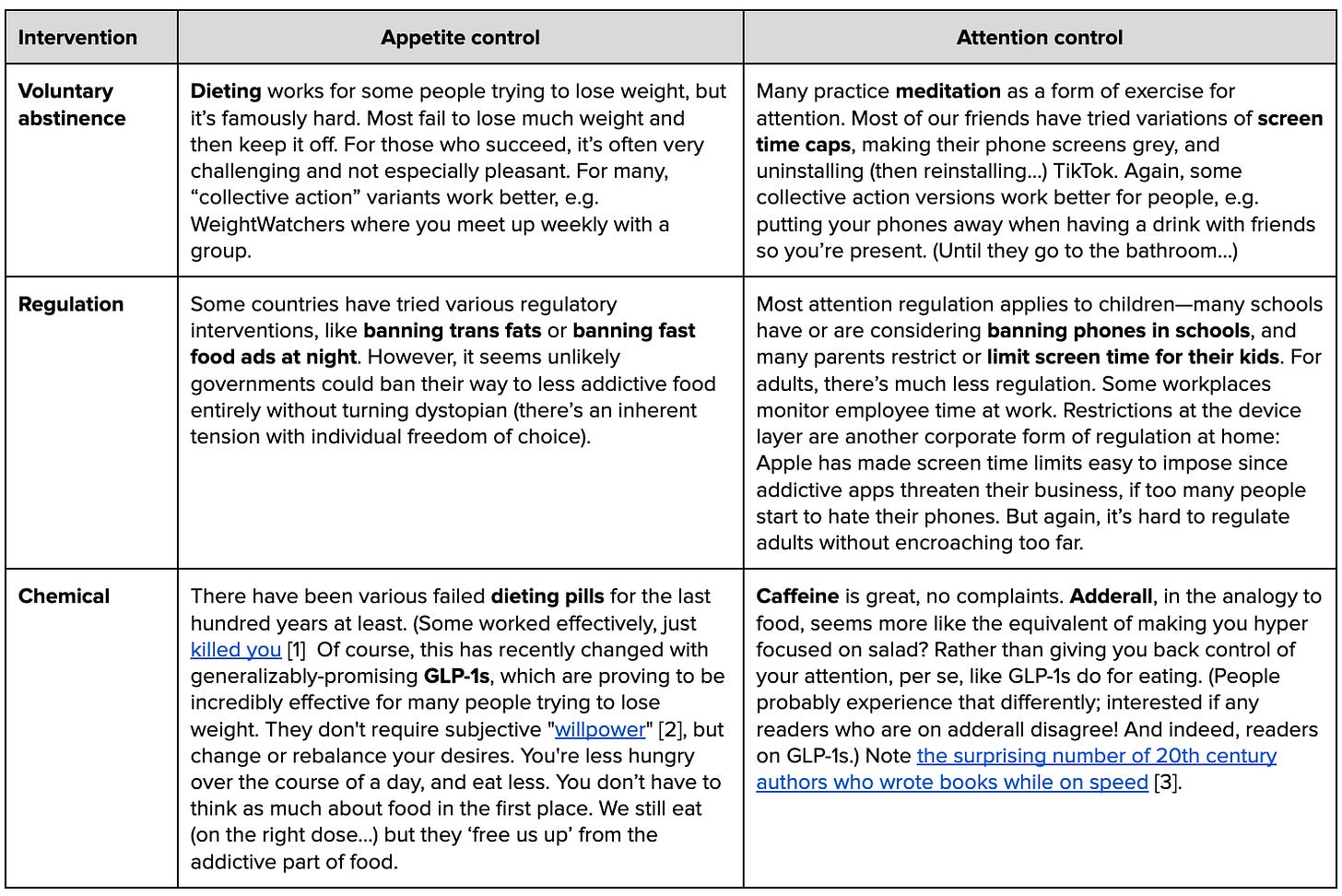

And finally, people try (and struggle with) similar types of interventions to control appetites as they do attention:

[1] Asimov Press, [2] Useful Fictions, [3] Slate

GLP-1s but for attention?

What do we take away from this comparison? A few things.

First, voluntary abstinence on its own is unlikely to work for everyone—either for food or for attention. It’s absolutely respectable and fine to keep trying the old fashion way for attention control, but it’s probably going to keep being really hard for people. We personally have found collective action versions with friends great for this when everyone’s bought in, but in reality they’re unlikely to scale all that much.

Second, there probably is a role for a bit more regulation, especially in schools. But it’s unlikely that gets us all the way there, and it’s trickier to get regulation right for adults without some outside force trying to ban something we actually want to do.

Third, this made us wonder: should there be a GLP-1-equivalent for attention?

“Isn’t that Adderall?” Not exactly. We don’t want to be hyperfocused all of the time. Instead we want to have more control of what we spend our attention on—to be less easily hijacked by the increasingly-addictive information around us. We want our attention to be more easily ‘directable’ to the things we want to spend it on.

“Don’t existing GLP-1s help with attention (and everything)?” Maybe! There’s a lot scientists don’t yet know about GLP-1s, including longrun effects on the brain (positive and negative). But GLP-1s were designed to curb appetite by doing things like slowing gastric emptying. While this may have positive spillover effects for attention, it seems plausible that an effort that’s dedicated to curbing attention might look different than today’s GLP-1s.

“You want more technology to save you from today’s technology? You want everyone to be on even more drugs?” Don’t take drugs you don’t want to, especially not hypothetical ones. But GLP-1s first came from lizard saliva, cocaine from leaves, and tomatoes are made of biological molecules. Life runs on chemistry; the point of this hypothetical chemical is to give people control over things they don’t otherwise. Technology is not all bad or good, modernity is not all bad or good. We’re glad the technology of coffee made it to Europe in the 17th century. It probably helped with some of their other problems.

So, if any scientists or psychiatrists are reading this….

Are there drugs that exist that already seem to you like “the GLP-1s for attention”? (Or indeed any surprising foods or vitamins that interact with attention?)

If not, could someone develop molecules that achieve the goals we really care about with respect to attention, better than what’s on offer?

Thank you for your attention on this matter.

As a person who’s been on Adderall for ~15 years, I respectfully disagree. Adderall precisely makes it easier to direct my attention where I want to, which includes the ability to pry myself away from hyperfocus (a symptom of ADHD, as you probably know) and survey the larger context. When people do use Adderall to hyperfocus, as I’ve also done at times, it’s much more of a choice (perhaps owning to a false scarcity mindset along the lines of “when else will I ever get another chance to make this much progress on something I care about”), rather than a compulsion.

As a person with ADHD, I have found that focusing has less to do with improving my ability to sustain keeping my attention on something, and more to do with not getting fully knocked off course by distractions. For example, it's one thing to get knocked out of a flow state because one of my roommates has opened or closed the door somewhere in the house. It's yet another to get a notification from Instagram and then start scrolling Instagram reels and then lose an hour of my time to something I didn't even care about. I am always capable of hyperfocusing on videogames if I so choose—but that's not a good thing.

(I've heard calls to rename ADHD to Attention Dysregulation Disorder, which I quite like. It's not like I have a deficit of attention—it's the regulation that's the issue.)

As Dr. Gena Gorlin said in another comment on this post, my ADHD medication doesn't directly make me more likely to hyperfocus: it makes it easier for me to ignore distraction. Our hypothetical attention drug would be the same. The ability to direct our attention wherever we want is less important than the ability to selectively dampen our curiosity or impulsiveness—but when I phrase it like that, it starts to sound somewhat less desirable.

Meditation is helpful for this, but I think there are also many different kinds of meditation, all with different aims. Not all of them are focused on training you to avoid distraction, and not all of them are specifically about tolerating boredom (which are two separate things anyway). For me personally, a combination of therapy, medication, and meditation has done wonders for my ability to regulate my attention. And during periods when I can't take my medication (this has been the last month for me because I've been sick), I really notice the increase in distractibility and boredom, and rely even more heavily on my habits built from therapy and meditation.